ABSTRACT

Within the underprivileged communities in the Philippines, maternal health issues arise in the context of systematic discrimination and inequity.

The stories of Glory-Jean Cabigon, Fredilyn Mangubat, Cresilda Palaca, and Rudilyn Amihan highlight their immense resilience and strength, as well as the urgent need that exists for restructuring welfare distribution in maternal healthcare.

METHODOLOGY

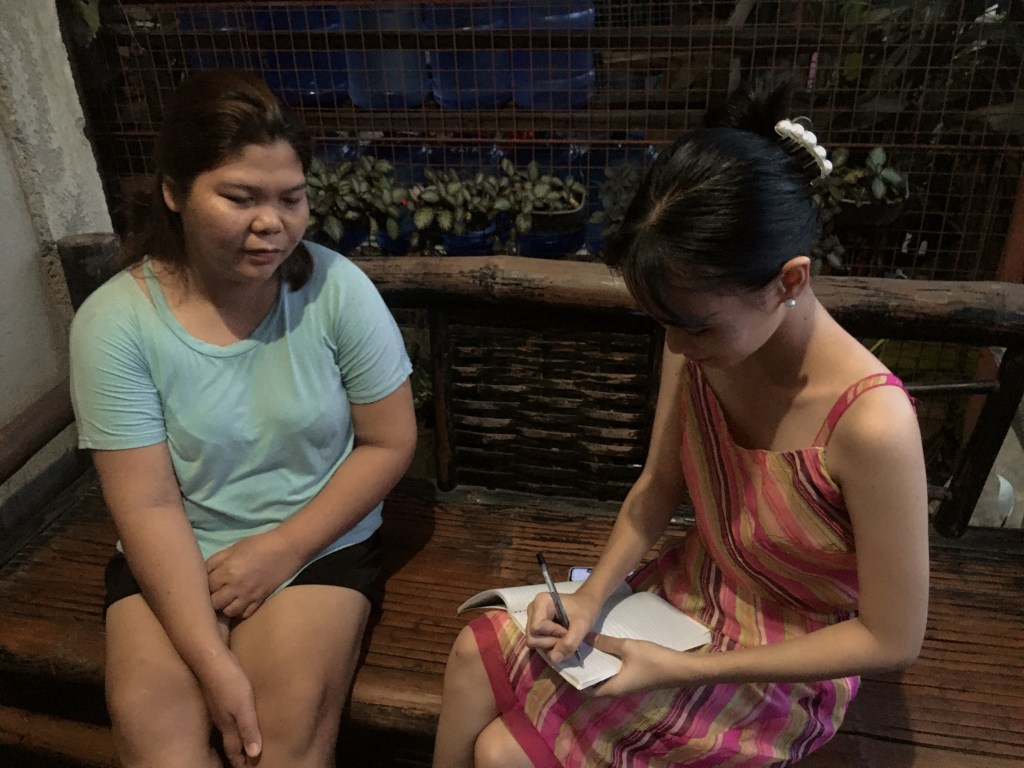

This article is based on qualitative interviews as its primary data collection method.

Four mothers from Barangay Dumarait who had recently given birth participated in individual and in-depth interviews.

In return for their time, they received groceries and basic necessities from YOHANNAN.

The interviews focused on the women’s narratives around their pregnancies, childbirth, and postpartum experiences.

Audio files were recorded and transcribed, along with consent forms documented accurately, capturing participants’ voices ethically.

Key issues such as the provision and utilization of healthcare services, social support, government aid, and participation from the local populace were explored using thematic analysis.

| Glory-Jean Cabigon: Youth Interrupted, Hope Reclaimed

When Glory-Jean turned 18, she had to drop out of school because she became pregnant.

Now, at 24 and with two children, she describes how she went back to school during the pandemic, motivated by a desire to pave a better educational path for her children.

Currently, she is a homemaker looking after the children while her live-in partner, who is a carpenter and labor worker, is the sole breadwinner of the family.

From the barangay health center, she got complete prenatal care, but the long lines and sluggish services made the care stressful.

The most lacking for her was government aid, which she felt was unavailable.

| “Wala kay kuan, kanang, gipili ra ang kuan… ang makadawat.”

(None because, uh, it’s like they only selected… who could receive).

Autonomous help, which in her case was her family and neighbors, despite the lack of formal support, became critical in illustrating an essential informal safety net.

Her story is in line with other research detailing rural maternal support system gaps (Baring et al., 2016; Ramirez et al., 2020).

| Fredilyn Mangubat: Blessings Later in Life and Gaps that Still Remain

Fredilyn’s story sheds light on mysteries that lie behind the veil of cultural norms and gendered fantasies surrounding motherhood.

Her journey began with two heartbreaking miscarriages, which many physicians caused by a weak uterus.

After a long and painful journey, Fredilyn was finally able to give birth to a healthy son after her third pregnancy.

Years later, to the surprise of the entire family, she gave birth to a baby girl.

This was in addition to the 16-year-old son she already had, so it truly felt like a gift for the entire family.

While her husband drove a jeepney, during that time she also sold food, which helped the family with their financial burdens.

She now has the luxury of being a full-time wife and mother.

The barangay health center received praise from Fredilyn for aiding her throughout her pregnancy, but medicine shortages caused her to travel to the Rural Health Unit (RHU), which is an added burden for already stressed-out mothers (Ramirez et al., 2020).

Most notably, she criticizes how government aid such as 4Ps and local ayuda (aid) are given out.

| “Ang ilang style sa ilang pagpanghatag sa ayuda, pinili ra, mao nang kami, dili jud mi maapil kay ang ilang mga ilista, kato ramang ilaha ra sang mga tao.”

(Their way of giving aid is selective, so we’re really not included because the people on their list are just their own people.)

She highlights the underlying issues associated with the aid that is provided—the problem is not solely the lack of aid but, rather, the lack of fairness in providing it (Romualdez, 2023).

| Cresilda Palaca: When Distance Determines Survival

Cersilda Palaca’s pregnancy with her fourth child was challenging for her.

She had to change hospitals in the middle of the night because the one in their town, Balingasag, Misamis Oriental Provincial Hospital, which is the nearest hospital from Barangay Dumarait at approximately 5.6 km distance.

This hospital lacked the necessary equipment needed to perform an emergency C-section.

She had to be urgently transferred to a bigger hospital in Cagayan de Oro City, Capitol University Medical Hospital, which is approximately 46 km away and would take about an hour and a half for an ambulance to get there.

This highlights the difficulties of having a complicated birth in a place where essential medical equipment needed for emergencies is unavailable.

Her husband drives a tricycle for a living, which amplifies the emotional burden of pregnancy complications due to lack of advanced maternal healthcare services nearby.

Aside from that, Cresilda also notes how she didn’t receive any ayuda (aid) postnatally due to inequity in the giving of necessary needs for the mothers.

| “Wala ko nila nalista.”

(They didn’t list me.)

She showed her dismay by admitting that she wasn’t listed, not that she didn’t choose to be a recipient; she just wasn’t given the opportunity to receive aid.

Government aid programs do exist, but many families like Cresilda’s are ineligible due to lack of connections or simply because those assigned to deliver the aid to the mothers have not done a great job doing so.

Why, you might ask?

Well, I believe that is a question only those in power can answer.

These situations demonstrate the very real issue of maternal mortality being affected by geography and discrimination rather than medical need (Combs Thorsen et al., 2012; Ramirez et al., 2020; SciDev.Net, 2024).

| Rudilyn Amihan: Balancing Family, Business, and Motherhood

Rudilyn Amihan is both a mother and a small business owner, running a sari-sari (grocery) store.

Her day starts before sunrise with tending to her two daughters, ages 14 and 11, one already in high school while the other is a graduating elementary student.

Her day ends well past sundown managing their small business.

She appreciates local health units for their support, but she notes how simply missing doses for prenatal care or needing to buy medications using her own pocket money can quickly add up to a lot financially.

She shared how she didn’t feel like she could fully rely on free health care access and had to take matters into her own hands, buying medications, among other things, personally.

Rudilyn shares the same sentiments as other people when talking about the government’s selective aid programs.

| “Way available kay wa man mi tabangi.”

(There’s nothing available because we weren’t given any help.)

In the absence of reliable government aid, she turns to her husband and relatives, but most importantly, her loyal customers from the community.

Though when asked about her hopes for better healthcare access, she mentioned how she would prefer if healthcare units had all the medications needed at all times, stating how medications are one of the most important healthcare factors that shouldn’t be overlooked.

| “Ang ayuda mawala raman na. Ang tambal… Mao nay mas tsada.”

(Financial aid disappears easily, but medicine… That’s what’s more important.)

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

Analyzing all four interviews revealed gaps and positive aspects regarding the maternal care system in rural areas such as Barangay Dumarait, Balingasag, Misamis Oriental.

It appears that all mothers received at least some form of prenatal care.

However, most reported experiencing delays, traveling for inadequate local services, or dealing with medication shortages (Ministry of Health, Japan, n.d.; Wulandari et al., 2021; Ramirez et al., 2020).

Above all, every woman underscored the critical concern of biased government assistance.

While programs such as 4Ps and local ayuda (aid) aim to serve at-risk families, their actual implementation is often stalled due to favoritism, nepotism, obsolete beneficiary lists, interfering politics, and other barriers (Paredes, 2016; Oñate, 2015; Baring et al., 2016; Romualdez, 2023).

COMMON THEMES

- Uneven Access to Maternal Healthcare

- Basic services are offered in most local health facilities; however, they are under-equipped and lack essential medicines (Ministry of Health, Japan, n.d.; Ramirez et al., 2020).

- Geographic and Logistical Barriers

- Cresilda and patients like her were not only far from adequate healthcare resources but also needed to be transported long distances for critical care (Combs Thorsen et al., 2012).

- Community Reliance

- Support provided to mothers was primarily through neighbors rather than government programs on an emotional and practical level.

- Bias in Aid Distribution

- All four mothers noted politically driven selective practices related to the distribution of ayuda (aid).

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Conduct Regular Audits of Beneficiary Lists

- Local government units should maintain regular and transparent audits of their aid distribution lists to eliminate bias and ensure equality.

- Allocate More Resources to Rural Health Centers

- Increase the budgets for rural barangay health centers to stock essential medicines and equipment.

- Improve Existing Community-Based Programs

- Equip local health workers with appropriate training and resources to provide better care for mothers.

- Establish Formal Channels for Complaints

- Safe channels need to be put in place for mothers to report exclusion from aid programs or bad service without fear of intimidation.

- Policy Reform Should Be Inclusive

- Voices from marginalized mothers need to be included in policy planning to better reflect ground-level realities.

CONCLUSION

| Listening to Mothers, Not Just Numbers

Every single statistic on maternal health has a story behind it: a woman’s life filled with navigating through sacrifice and uncertainties.

As the mothers from Barangay Dumarait illustrate, while there is government support, the uneven provision of services undermines their primary intention.

Their narratives are not mere accounts of struggle; rather, they are rallying cries to broaden the scope of compassion and inclusivity and elevate justice at the very least in maternal care (Oñate, 2015; Paredes, 2016; Wulandari et al., 2021; Ramirez et al., 2020; Romualdez, 2023).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author would like to extend his profound gratitude to Glory-Jean Cabigon, Fredilyn Mangubat, Cresilda Palaca, and Rudilyn V. Amihan—the mothers of Barangay Dumarait—because of their openness regarding their own experiences in life.

This study would not have come to be without them.

Much respect and gratitude also to local health workers and residents in the area who supported the endeavor.

Special thanks to Hon. Edgardo O. Olano, Barangay Chairman of Dumarait, for the beautiful welcome and accommodation.

Also, thanks to the rest of Barangay Dumarait for their hospitality and support.

References

Baring, J. R., Ulep, V. G., & Dela Cruz, N. A. (2016). Inequality in the use of maternal and child health services in the Philippines: Do pro-poor health policies result in more equitable use of services? https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27832778/

Combs Thorsen, V., Sundby, J., & Malata, A. (2012). Piecing together the maternal death puzzle through narratives: The three delays model revisited. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23284882/

Ministry of Health, Japan. (n.d.). Country report – Philippines.

Oñate, K. (2015, May 19). Challenges in maternal health in the Philippines. Rappler.

Paredes, K. P. P. (2016). Inequity in maternal and child health care in the Philippines. International Journal for Equity in Health.

https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12939-016-0473-y

Romualdez, E. A. (2023). UHC goals aim to address inequities in maternal and child health. Philippine Council for Health Research and Development.

SciDev.Net. (2024). Philippines struggles to lower maternal mortality.

Wulandari, R. D., Laksono, A. D., & Rohmah, N. (2021). Urban–rural disparities in antenatal care utilization in Indonesia. BMC Public Health, 21, 1044.

https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-021-11318-2

Carrying more than life: Four mothers, one struggle for equity and care

Leave a comment